ADC Hall of Fame

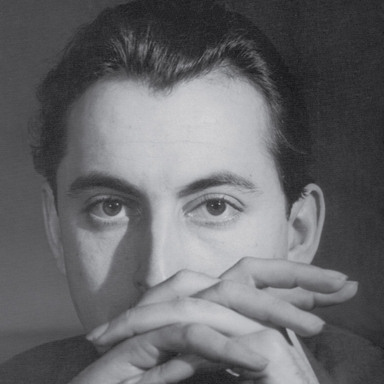

Alvin Lustig

Feb 8, 1915 - Dec 5, 1955

Inducted: 1986

With the current interest in American design history, it is fitting that Alvin Lustig be honored for his significant influence on American design and design education. His wide-ranging work from the 1940s and early 1950s included book and book jacket design, magazines, letterheads, catalogs, signage, furniture and lighting, textiles, interior design, logos, identity programs, sculpture and architecture. This diversity mirrored a philosophy that eschewed specialization and embraced synthesis. For Lustig, all design projects involved problem solving and all solutions were found in form and color.

Lustig's approach to design reflected the Bauhaus tradition of integrating fine and applied arts, of wedding technology with artistic creativity. Since he regarded differences in projects as largely technical, a designer had to develop and maintain a high standard of design, which could be successfully applied to any medium. The designer's task, no matter what the project, was to use words, forms and color to create a harmonious whole, more powerful than any single element. For Lustig, creating form was simultaneously to create content. While rooted in a tradition of design orderliness and complementarity, Lustig was an experimenter who played with and altered forms, cautioning against settling into a routine format. His strategy incorporated a respect for simplicity, for the need to eliminate design elements not contributing to the force of the image. Lustig set definite and universal criteria for good design, but looked to technology to offer unlimited opportunities for achieving visual excellence.

Lustig had an intellectual approach to design problems, which he said were solved more often in the head than anywhere else. He was known to spend days thinking about a project before putting anything down on paper. He was a voluminous reader on a variety of subjects and possessed a broad knowledge of painters and painting. All this background information was brought to an assignment as well as the need to research the particular project. When designing a book jacket for example, Lustig would read the text first, so that his design better represented the feel of the literature.

Lustig was an active proselyter of good design who regarded the public as "form blind" and insistently reprogrammed his clients. When publisher Ward Ritchie invited Lustig to share studio space, Lustig redesigned Ritchie's office. Likewise, when Arthur A. Cohen, President of Noonday Press, hired Lustig as a jacket designer, Lustig attempted to redesign the entire publishing firm. The designer felt the more information a client had, the better informed his or her decision would be. The client was responsible for self-education in order to select quality design talent.

Lustig's success in converting clients and his drive to improve the visual environment was paralleled in his effectiveness as a teacher during the same years, 1937 to 1955. For someone so passionately involved in design education, Lustig had only one year of formal training, at the Art Center School in Los Angeles. He didn't think it possible to teach creative art but he did think it possible to teach awareness. He looked to the campus as an area for experimentation and research not possible in the working world, the results of which could lead business and industry. Lustig lobbied for education programs which combined creative pursuits with technical instruction and which balanced the theoretical with the practical. In addition to studio courses on color and form, he advocated for proof presses, printing equipment and darkrooms as well as workshops conducted by leading professionals immersed in the "real" world.

One of the most influential of Lustig's educational activities was the design program he helped develop for Yale where he had begun teaching in 1951 as Visiting Critic in Design. Lustig felt the best design programs were affiliated with the best painting programs. The painter generated private, subjective symbols while the designer produced objective, public symbols. The interaction of the two would result in design with an ideal balance of originality and universality. The design program for Yale grew out of a 1945 summer course that Lustig conducted at Black Mountain College in North Carolina which was based on the teachings of artist Josef Albers. Lustig also developed a proposal for a design school at the University of Georgia and taught at the Art Center School in Los Angeles and the University of Southern California.

Originally from Denver, Lustig moved to Los Angeles as a child and there began his design career. In 1933, at the age of eighteen, he became art director of Westways Magazine published by the Automobile Club of Southern California. In 1935 he studied for three months with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin and in 1936, with Jean Charlot, the Mexican fresco artist. Between 1937 and 1944, Lustig operated his own typographic and printing business where he experimented with standard geometric type ornaments for printed pieces and books, much of it for Ward Ritchie Press. In the early forties, James Laughlin ofNew Directions Booksin New York began to commission jacket designs which earned for Lustig an international reputation.

He left Los Angeles for New York in 1944 to create a visual research department for Look Magazine while continuing a freelance practice. In 1946 he returned to LA to open a design office and took on a variety of projects including several stores, an apartment hotel and even a molded plywood helicopter. Lustig returned to New York in 1951 where he continued to involve himself in diverse assignments, from book jackets for Noonday Press to an architectural identification program for Northland shopping center in Detroit. His work was exhibited at the American Institute of Graphic Arts, the AD Gallery in New York, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and the Museum of Modern Art.

Articles by and about Lustig appeared in most every major design periodical in the 1940s and 1950s:American Artist, New Furniture, Print, Architectural Forum, Arts and Architecture, Graphis, Interiors, American Fabric, Progressive ArchitectureandArt News. Among his awards were Fifty Books of the Year Award from the AIGA, numerous Awards of Merit from the AIGA and the Good Design Award, for chair design, from the Museum of Modern Art. His work is in the permanent collections of the UCLA Clark Printing Library, Rochester Institute of Technology and the Museum of Modern Art.

Lustig possessed what he described as "a very high standard of dissatisfaction" and strove relentlessly for order and harmony in his own design and in others. So keen was his vision of the power of design, he thought it a force capable of bettering society. In his short, forty-year life, Lustig produced a prodigious amount of work and pioneered a comprehensive approach to design, which will last far beyond his lifetime. His work is as vibrant today as it was forty years ago. From the International Style, Lustig forged a distinctive American design aesthetic of timeless beauty and technical virtuosity.

Please note: Content of biography is presented here as it was published in 1986

Lustig's approach to design reflected the Bauhaus tradition of integrating fine and applied arts, of wedding technology with artistic creativity. Since he regarded differences in projects as largely technical, a designer had to develop and maintain a high standard of design, which could be successfully applied to any medium. The designer's task, no matter what the project, was to use words, forms and color to create a harmonious whole, more powerful than any single element. For Lustig, creating form was simultaneously to create content. While rooted in a tradition of design orderliness and complementarity, Lustig was an experimenter who played with and altered forms, cautioning against settling into a routine format. His strategy incorporated a respect for simplicity, for the need to eliminate design elements not contributing to the force of the image. Lustig set definite and universal criteria for good design, but looked to technology to offer unlimited opportunities for achieving visual excellence.

Lustig had an intellectual approach to design problems, which he said were solved more often in the head than anywhere else. He was known to spend days thinking about a project before putting anything down on paper. He was a voluminous reader on a variety of subjects and possessed a broad knowledge of painters and painting. All this background information was brought to an assignment as well as the need to research the particular project. When designing a book jacket for example, Lustig would read the text first, so that his design better represented the feel of the literature.

Lustig was an active proselyter of good design who regarded the public as "form blind" and insistently reprogrammed his clients. When publisher Ward Ritchie invited Lustig to share studio space, Lustig redesigned Ritchie's office. Likewise, when Arthur A. Cohen, President of Noonday Press, hired Lustig as a jacket designer, Lustig attempted to redesign the entire publishing firm. The designer felt the more information a client had, the better informed his or her decision would be. The client was responsible for self-education in order to select quality design talent.

Lustig's success in converting clients and his drive to improve the visual environment was paralleled in his effectiveness as a teacher during the same years, 1937 to 1955. For someone so passionately involved in design education, Lustig had only one year of formal training, at the Art Center School in Los Angeles. He didn't think it possible to teach creative art but he did think it possible to teach awareness. He looked to the campus as an area for experimentation and research not possible in the working world, the results of which could lead business and industry. Lustig lobbied for education programs which combined creative pursuits with technical instruction and which balanced the theoretical with the practical. In addition to studio courses on color and form, he advocated for proof presses, printing equipment and darkrooms as well as workshops conducted by leading professionals immersed in the "real" world.

One of the most influential of Lustig's educational activities was the design program he helped develop for Yale where he had begun teaching in 1951 as Visiting Critic in Design. Lustig felt the best design programs were affiliated with the best painting programs. The painter generated private, subjective symbols while the designer produced objective, public symbols. The interaction of the two would result in design with an ideal balance of originality and universality. The design program for Yale grew out of a 1945 summer course that Lustig conducted at Black Mountain College in North Carolina which was based on the teachings of artist Josef Albers. Lustig also developed a proposal for a design school at the University of Georgia and taught at the Art Center School in Los Angeles and the University of Southern California.

Originally from Denver, Lustig moved to Los Angeles as a child and there began his design career. In 1933, at the age of eighteen, he became art director of Westways Magazine published by the Automobile Club of Southern California. In 1935 he studied for three months with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin and in 1936, with Jean Charlot, the Mexican fresco artist. Between 1937 and 1944, Lustig operated his own typographic and printing business where he experimented with standard geometric type ornaments for printed pieces and books, much of it for Ward Ritchie Press. In the early forties, James Laughlin ofNew Directions Booksin New York began to commission jacket designs which earned for Lustig an international reputation.

He left Los Angeles for New York in 1944 to create a visual research department for Look Magazine while continuing a freelance practice. In 1946 he returned to LA to open a design office and took on a variety of projects including several stores, an apartment hotel and even a molded plywood helicopter. Lustig returned to New York in 1951 where he continued to involve himself in diverse assignments, from book jackets for Noonday Press to an architectural identification program for Northland shopping center in Detroit. His work was exhibited at the American Institute of Graphic Arts, the AD Gallery in New York, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and the Museum of Modern Art.

Articles by and about Lustig appeared in most every major design periodical in the 1940s and 1950s:American Artist, New Furniture, Print, Architectural Forum, Arts and Architecture, Graphis, Interiors, American Fabric, Progressive ArchitectureandArt News. Among his awards were Fifty Books of the Year Award from the AIGA, numerous Awards of Merit from the AIGA and the Good Design Award, for chair design, from the Museum of Modern Art. His work is in the permanent collections of the UCLA Clark Printing Library, Rochester Institute of Technology and the Museum of Modern Art.

Lustig possessed what he described as "a very high standard of dissatisfaction" and strove relentlessly for order and harmony in his own design and in others. So keen was his vision of the power of design, he thought it a force capable of bettering society. In his short, forty-year life, Lustig produced a prodigious amount of work and pioneered a comprehensive approach to design, which will last far beyond his lifetime. His work is as vibrant today as it was forty years ago. From the International Style, Lustig forged a distinctive American design aesthetic of timeless beauty and technical virtuosity.

Please note: Content of biography is presented here as it was published in 1986